Mission to serve

Posted: May 13, 2014

The United States military is comprised of extraordinary men and women who selflessly serve for the greater good of this great country. Many of these individuals are also ATSU alumni, specializing in various aspects of military medicine, attending to the complex healthcare needs of service members in all branches of the armed forces. They serve bravely on the front lines, where indescribable soldier trauma is all too familiar. They serve quietly behind the scenes, planning intricate medical missions at home and abroad. They are innovators, taking military medical technology and knowledge to the highest levels. Their personal military stories, heart-wrenching and raw, define humble heroism. As they carry out their missions, changing lives across the world, their lives, too, are forever changed.

~~~

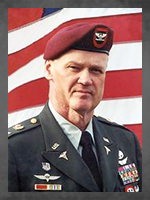

One of four military physicians on a three-week humanitarian mission aboard a small Peruvian Naval vessel in 1989, Col. Jimmie D. Coy, DO, ’73 (Ret.), recounts how he helped save the life of a young boy facing near death. Dr. Coy never lost faith that the child’s health would be restored.

Dr. Coy remains a medical consultant for the U.S. Army Special Operations Command. He served two years as national president of the Special Operations Medical Association and as national surgeon of the Reserve Officers Association, as well as with numerous Special Forces and Special Operations units, notably the 3rd Group Army Special Forces (Airborne) in the 1991 Gulf War. He has received a myriad of military honors, awards, and badges, including the Legion of Merit, the Combat Medical Badge, and the prestigious “A” designation—the highest recognition of the Army Medical Department.

Dr. Coy chronicles his military experiences as the author of a series of books addressing leadership, courage, hope, and faith, which can be found at www.agatheringofeagles.com.

Miracle on the Amazon

The trip from San Palo was long and we arrived at dusk at the small village of Triumfo. A family rushed up with their young boy who was extremely sick. He had been vomiting and had diarrhea for many days. As I pinched the skin on his abdomen, the skin remained raised in an elevated mound. My suspicion of profound dehydration was confirmed. We knew the child would not survive without intensive medical intervention, but no local care was available.

The medical supplies on board the vessel were very limited, so we decided to take the sick child and his family to a small, but primitive, Peruvian hospital about four hours down river. We only had a few IV solutions, some IV tubing, and needles. The youngster was so sick, and his dehydration so severe, that he was almost unresponsive. As we started down the river, the two Peruvian physicians tried to start an IV on the child. After many unsuccessful attempts, they asked the other American physician to try. Despite numerous attempts, he too was unable to start an IV. As each minute passed, the child seemed less responsive even to the painful needle sticks. He was moving closer to death.

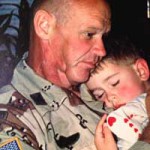

Dr. Coy holds son Josh after returning from the Persian Gulf.

As his pulse weakened and his rapid heart rate became faint, I lifted his eyelids and saw his eyes were rolled back in his head and his pupils appeared dilated. We were weary from the long day, but there would be no rest. We knew if we did not get fluid into the child that he would die. The two Peruvian physicians re-examined the child and agreed with us that death was imminent and proceeded to inform the family that we were unable to save the child. The mother began to quietly sob, as did the boy’s siblings as they surrounded the dying child. The father sat quietly watching. Just looking at his face, you could see the pain and tell that his heart was breaking. The other American physician headed for the door, trying to hide his tears and silence his own grief.

The youngster’s vascular system was collapsing. There seemed to be no vein that we could use. The thought came to me that if I could just get a needle into the faint and barely palpable femoral artery, near the groin, that maybe there might be a slim chance of saving him.

WEB EXCLUSIVE See more behind-the-scenes photos from these alums here.

As I felt for the pulse of the femoral artery, I began to recite to myself Psalm 91, the soldier’s psalm. As I finished the verse, I stuck the needle once again into the almost lifeless child. Arterial flow; it worked.

We compressed the IV bag and began administering fluids. After an hour passed, the arterial line stopped flowing; it wasn’t working. Once again I searched for a vein to use. I noticed a small one above the child’s ear. Again I prayed the words in Psalm 91 and was able to start an IV.

After midnight we finally reached the small village and began our trip carrying the child on winding, narrow paths through the dark jungle to the hospital. On the way, the IV line was accidentally pulled out, and our hopes dashed once again. When we arrived, the caretaker told us that a part-time physician and a nurse staffed the hospital but would not return until morning.

We gently placed the child on one of the few beds. With another prayer, I was able to start the final IV by the light of a flashlight one of the others held. At that point there was nothing more that we could do for the boy. We left him in the hospital and headed back through the hot, sticky darkness of the jungle.

When I climbed into my bunk, I thought about home. Exhausted, I finally fell asleep.

When I awoke, the other American physician came by and told me the news: Not only was the child alive, he was awake in his mother’s arms, talking, and drinking fluids! He was alive!

~~~

COO for the Coast Guard Health Services,

Dr. Cannon additionally extends his service to

ATSU as vice chair of its Board of Trustees.

James D. Cannon, DHA, PA-C, MS, ’97, is chief operating officer for Coast Guard Health Services and oversees physicians, PAs, dentists, corpsmen, and techs at 45 clinics in 13 regions. In the U.S. Coast Guard, Dr. Cannon served as chief physician assistant and consultant to the USCG surgeon general and chief medical officer. He also was responsible for the program that trains Coast Guard PAs and served as the agency’s medical contingency planner. In 1997, just six months after graduating from the first PA class at ASHS, Dr. Cannon was mobilized to a draught-stricken, remote Polynesian island where he was the only U.S.-trained provider as part of a multi-service engineering team comprised of members from the Army, Navy, and Air Force. Unfazed by the enormity of his mission, he heralds his comprehensive training for his readiness.

“Semper paratus”: Always ready

Pohnpei at the time was probably 20,000 people, and about 40 percent of the population was under 18 years of age. It was a tropical paradise with mangoes, papayas, and yellow fin tuna swimming out in the water, but it was underdeveloped. I was a brand new graduate PA using remote supervision of physicians and had very complex cases. I was well-trained and well-prepared. For seven months, I took care of truly everything under the sun from the very young to the very old with very few diagnostics. You couldn’t be in more of an underserved population.

I worked in their version of an emergency room, which was an open air hospital—very low-tech. It wasn’t much more than a set of exam rooms. A case came in. I remember a young 14-year-old kid, just barely able to walk. He’d take a few steps, stand and rest, his dad helping him. I had been on the island for about three weeks. He came to see me because he had seen all the other doctors there and didn’t know what to do.

The kid approached, and I saw some distention on his neck vein. I barely got the stethoscope up to his heart and knew right away he had a bad mitral valve regurgitation. His mitral valve was not working. I asked him how long he’d had it, and he said about a year. I asked him what other complaints he had. He said his knees hurt, his back hurt. He recently had strep throat … The strep infection disseminated down his neck and eroded his heart valve. He met the Jones criteria for mitral valve dysfunction secondary to strep infection. They just didn’t put the pieces together. I got on the phone, did a telephone/email consult with Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii, and two weeks later we got him on a plane and to a pediatric surgeon who replaced his valve. He was back on the island eight weeks later, doing great.

~~~

Dr. Barbabella

After multiple deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, CAPT(sel) Sean P. Barbabella, DO, ’96, compares his experiences and is especially grateful for the camaraderie among Marines. Dr. Barbabella is highly decorated, having received the Legion of Merit on his second tour in Afghanistan and a Navy and Marine Corps Commendation with combat valor. He was awarded a Purple Heart for his 2009 Afghanistan tour where he sustained wounds in an IED explosion and was a pioneering physician of the Mobile Trauma Bay, a large armored vehicle used in combat to provide ER-level care to wounded on the battlefield.

Personal combat, personal care

In ’09, it was very kinetic. I was in a total of three IED blasts. Luckily, I was in armored vehicles. In one, I got a concussion and a shoulder injury. It was an interesting dynamic—different than my other deployments because I was with a small company of about 300 Marines and we were surrounded on three sides by the enemy. Our unit was in fire fights or engagements daily. Any time I went out to pick up a casualty, and any time someone would step on an IED, that’s when an engagement would start because the enemy knew we were at a disadvantage. I had a side arm and an M4 for protection of my patients and my personal safety. We were in combat almost all the time when we went “outside the wire.”

There was a six-week period where we took multiple contacts daily—mortars, rockets, and machine gun fire into our outpost. The first night it was hard to sleep, but then I quickly came to the realization that I am here to do my mission and can’t worry about all this other stuff. At one point, almost every vehicle we had except the medical vehicles was destroyed. Then, my vehicles started getting blown up.

Dr. Barbabella

I was told to never get out of the medical vehicle. One day, we were stuck in a wadi, and I saw all the Marines getting out. I know they said never get out, but when the gunners are getting out of the top of the vehicle, something’s not right. They yelled, “Run, mortars walking in on our vehicle!” I started running, and one of the Marines grabbed me and said, “You’ve got to run behind me, Doc. If I step on an IED, that’s OK, but you can’t.”

It’s just the thought process that once you knew these guys, how much they went out of their way to protect you. Even though they knew they could get injured, they thought if the doctor gets injured, that limits everyone. Our combat outpost was very small, maybe a football field long and wide. You knew every casualty you took care of. There was a difference—they knew you, you knew them, they were your friends. You provided far forward cutting-edge trauma care either way, but it was definitely more personal. You fought for the guys you were with.

One of the guys I took care of, Sgt. Josh Sweeney, was a double amputee. It was a long day. We started to do the medevac. Our convoy hit multiple IEDs, we lost three vehicles, and we started taking direct fire. We lost a Marine trying to rescue these guys. Fast forward and Sweeney is a paralympian who scored the only goal to win a gold medal for Team USA in the March Sochi, Russia, Paralymipics as a forward on the sled hockey team. Coincidentally, Sweeney’s teammate, Paul Schaus, is another Marine my team took care of in Now Zad, Afghanistan. These are the truly amazing heroes; they are why we do what we do.

~~~

Dr. Silverton

Col. Craig D. Silverton, DO, ’78, retired from the U.S. Air Force Reserves after 30 years of service. He spent 10 years as a pararescue officer and several years on active duty working with an elite counterterrorism unit. He did two tours in Iraq as a combat surgeon and one tour in Afghanistan. Stationed on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan, he was sent into the Afghan mountains to evaluate trauma care by a local Afghan military hospital, which he describes as a “wild experience.” The following excerpt is from Dr. Silverton’s time log in May and June 2010.

Into the Afghan mountains

The base is large and surround by Constantine wire like most bases. Outside the wire are mud walls—almost like mud cities. That’s where the Afghans live. No electricity and no water. An ancient living people—like they lived 1,000 years ago. The ability for the Afghans to come right up to the wire/perimeter is unlimited. Kids are cute with their little outfits. Seem just like normal kids, but playing with their goats and sheep. Such a different way of life.

They have an opportunity to jump over the fence and use cardboard to lie over the wire and come on in and join the 30,000- 40,000 folks who are already here. So many local nationals walking around, you would have no idea who is who. I have the feeling they hate us for invading their country. Although they don’t mind our medical care! They will drive hundreds of miles through mine infested roads to get here and pay $300-$400 for a cab ride that takes two days for a 15-minute visit. Most are postoperative checks from IED or GSW, which we operated on at some time. If the Taliban finds out they go to an American outpost, they will be killed, along with their family.

Dr. Silverton teaches Afghan surgeons how to make antibiotic beads for the treatment of infections.

Very interested in what our role will be in training the Afghan surgeons. No real program is put together yet. I question the real commitment that they have in this endeavor. And do I want to be a part of this training, or is it a lost cause? Working with the surgeons at Gardez was interesting, but day-in and day-out would get old. The chiefs at Gardez have their own ways of doing things. Not sure they are interested in our training their surgeons in the U.S. ways. Not really sure how open they are to this. Maybe they fear for their jobs? Not sure, but the younger surgeons are very anxious to be able to operate on their own. This would require lots of training. They really have not had a residency and trying to make them into surgeons (general or orthopedic) without the required residency may be a bit too much and expectations are unrealistic.

~~~

Mission accomplished

Boots on the ground and missions accomplished, military medicine is not for the faint of heart or the faint of skill. When faced with uncertainty and danger—when lives are in the crossfire—ATSU’s military service alumni are able to make the best out of a bad situation. Their personal stories amply tell of their drive, ingenuity, and passion for doing good. ATSU is honored to be a part of their healthcare training and proudly salutes those who serve.